Queen Elizabeth's Passing and the Difficult Legacies of British Empire.

A guest post by Bill Emmott, former editor-in-chief of The Economist

Welcome back to Lucid. There will be no Q&A this Friday since I am in Sydney giving a keynote speech on “The Return of the Strongman” at the Festival of Dangerous Ideas. We will resume our Friday meetings on September 23. Paying subscribers will receive a link to register that morning.

The passing of Queen Elizabeth II has brought forth floods of emotion. Grief at the loss of a monarch who was an anchor for so many; anger at the veneration of the head of a murderous colonial empire; nostalgia for traditions and institutions that some see as anachronistic and others see as essential to Britishness even today.

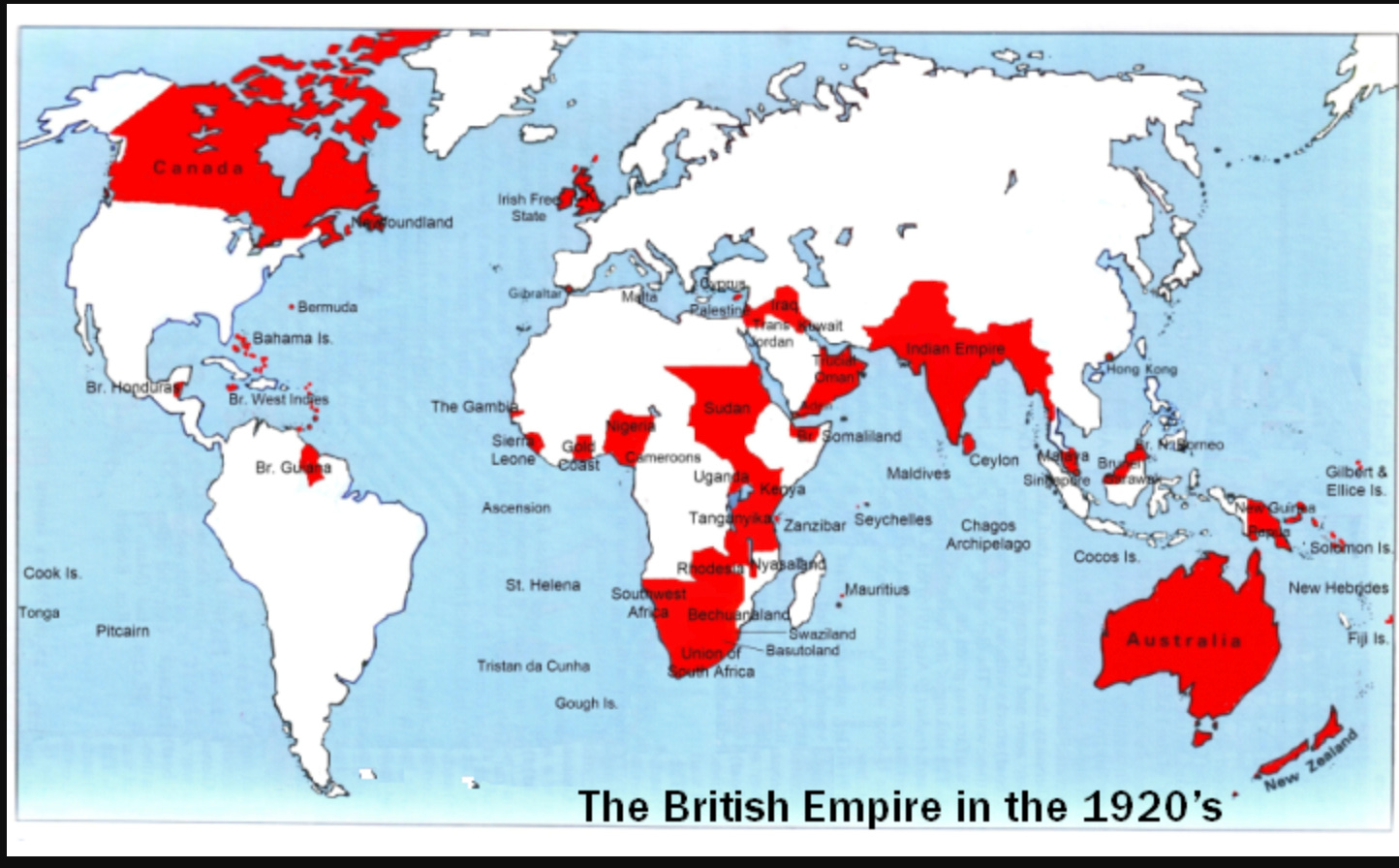

The British empire at its peak was the largest empire in world history, governing 458 million people. The traumatic effects of colonial rule are felt by millions today, and the influence of the empire among those who supported it or simply grew up with it as part of their country’s identity extended through generations and to unexpected places.

Although I grew up in California, the Queen and the British empire were part of my family history. The Queen was a benevolent presence in our home, since my Scottish mother and all of my Scottish and English relatives admired her enormously. In 1953, while working as a young secretary in London’s Oxford Street, my mother had seen the Queen pass by in her golden coach on her way to her coronation. That magical moment forged a connection, and over the years my mother wrote to the Queen many times, always receiving a reply.

On the Middle Eastern side of the family, my grandfather, who was born in Aden when it was a British colony, served the empire there and in Kantara, Egypt, as a police inspector. Such colonial intermediaries, drawn from the local population, were essential to the maintenance of empire.

To illuminate what the Queen’s passing means for Britain and its imperial legacies, I am publishing Lucid’s first guest post, by Bill Emmott, former editor-in-chief of The Economist. This piece, which was written for the Italian newspaper La Stampa, appeared in his own terrific Substack newsletter, Bill Emmott's Global View, which covers foreign policy.

__________________________

The Long Century of Queen Elizabeth II

To citizens of her United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, Queen Elizabeth II represented a sense of continuity with the country’s history, and above all a sense of selfless duty and decency. Her 70 year reign had seen 15 prime ministers come and go, including the replacement on September 6 of Boris Johnson by Liz Truss, and it is safe to say that the Queen’s reputation with the British public remained far better and warmer than any of theirs, with the possible exception of her first prime minister, Sir Winston Churchill.

To the world, however, she and the British monarchy she served symbolised something deeper and broader. Continuity, yes, for simply having been such a constant figure in an always changing scene, but also a connection to Britain’s history in both a negative way and a positive one.

The negative aspect is that her birth in 1926 but even more so her succession to the British throne in 1952 took place at a time of empire, when Britain’s empire indeed was still the world’s largest. In fact she learned of the death of her father King George VII, and hence her accession to the throne, while on holiday in Kenya, which was then a British colony.

That British empire was almost completely dismantled during the following decades, culminating in the return of Hong Kong to Chinese rule in 1997. Yet protests and controversy about the legacy of empire still occur, for example during the visit last May to some Caribbean former colonies by her grandson, Prince William, amid claims in some of those countries for the payment of reparations for the slavery used by the empire especially during the 18th century.

With that negative memory of empire, which is also perpetuated by the honours the Queen has had to bestow formally several times a year with names such as “Order of the British Empire” (OBE), comes also a reminder of how much Britain’s role and power in the world has declined during her reign. Normalised might be a better term, especially for the way Britain changed and behaved during the four decades during which the U.K. was a member of what is now the European Union. A country which in Queen Elizabeth’s youth had been an imperial force, largely promoting its own interests and bossing colonies around, became much more collaborative with others, through NATO, the EU and various UN bodies.

Sadly, there is no doubt that nostalgia for the imperial era lay behind some of the desire among political elites to leave the EU with the 2016 referendum and to “take back control”, as the Brexiters’ slogan said. The Queen’s personal opinion on Brexit is not known, of course, but it is nevertheless clear that the sort of aristocratic British society that is still centred on the Royal Family contains a lot of people who will have favoured Brexit.

The positive aspect of the Queen’s connection to British history is, however, that both she and the monarchy symbolise and even embody a strong tradition of pragmatism. Nothing could seem more English than the Royal Family, and yet for more than three centuries our monarchs have all been imported from European dynasties, first from the Netherlands (William III in 1689), and then two linked German families, the Hanoverians (from George I in 1714) and then the house of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha from 1901, from which Queen Elizabeth herself was descended.

Alongside that import by the English Parliament of European dynasties to occupy the throne came a steady erosion in the political and legislative powers of the monarch. Very plainly, Queen Elizabeth understood right from her succession in 1952 that her primary obligation was to remain silent on any and all issues of political controversy. This was not new: my distinguished forebear as Editor of The Economist, the Victorian writer Walter Bagehot, wrote in his 1867 book “The English Constitution” that the role of the monarch was “to be consulted, to encourage and to warn”, and nothing more than that.

By the 1950s, even the right to encourage and to warn had pretty much disappeared. The Queen was still “consulted”, by means of regular visits by the prime minister, but there is little evidence that these conversations have ever influenced government policy, even though in recent decades Queen Elizabeth was a lot more experienced in national and global affairs than were any of her prime ministers.

Both she and they knew that her role was to be a symbol of the nation, and in troubled times a comfort to it, but not to perform any even remotely political role of the sort played by other Heads of State. This poses something of a problem in a modern Britain in which prime ministers such as Boris Johnson have succeeded in undermining traditional rules and conventions that aimed to constrain their executive power. For where other Heads of State can act as checks or balancers, in Britain we have a constitutional vacuum.

That role of being purely a very dutiful symbol will continue under King Charles, but with a less global role. When Queen Elizabeth succeeded to the British throne, she was also Head of State of more than 30 other countries. During her reign, 17 of those chose to replace the British monarch with their own Head of State, most recently Barbados in 2021. With King Charles’s succession, many of the 14 remaining former colonies over which he will nominally reign, which include Canada and Australia, are likely to take the opportunity to replace him with a system of their own.

That, if it happens, will be a further form of normalisation, both for the British monarchy and for the U.K. itself. That normalisation is unlikely in the near future to include removal of the monarchy, for it remains popular as a symbol of history and a source of glamorous celebrity, and it would be very hard to secure political agreement on how best to replace it with another sort of Head of State.

The paradox of Queen Elizabeth II is that a woman who was required by her role to be largely silent and to hide her own personality came to represent such a strong image of continuity and history, thanks to her longevity. She had her troubled moments, notably the collapse of three of her four children’s marriages, and the shocking death of her heir’s then ex-wife, Diana, almost exactly 25 years ago brought a brief period of unpopularity. But the principle of personality suppression still held, enabling her popularity to recover.

King Charles comes to the throne at the age of 73 with the disadvantage that the public thinks they know quite a lot about his personality, thanks to the tragedy of Diana and to views he has made public in the past about the environment and about architecture. He will now have to suppress that personality and those views.

By no fault of his own, however, the British monarchy will now look a somewhat diminished entity, for it has lost that 70 years of continuity, duty and decency his mother came to represent. She will not just be a hard act to follow, but an impossible one.

Thank you for sharing those thoughts on QE2 and also about the mostly former British empire. Indeed America has/had an empire of its own, mostly through our many wars. Lots to think about.

Thank you for this!! The Queen's coffin was draped in the Royal Standard flag that has four quarters representing England, Scotland, and Ireland, and is never at half-staff as the "Union Jack" can be, as the UK is never without a King or Queen. The Queen's seven car cortege at first travelled through the Scottish Highlands and extended from Balmoral Castle to Edinburgh and then Buckingham Place and Westminster Hall for a state funeral .............with flowers and well wishers all along the way. Amazing!!!!