When Harlem and Little Italy Clashed over Ethiopia

This essay adapts an op-ed I published in the Washington Post in 2020. I’ve added new research and photographs that open a door onto a world of activism sparked by the 1935 Italian invasion of Ethiopia.

On Aug. 3, 1935, 25,000 Black and White New Yorkers marched down Harlem’s Lenox Avenue to protest Fascist Italy’s plans to invade Ethiopia, a League of Nations member and one of the few African nations that had never been colonized. The demonstration brought together Black labor, religious and pan-Africanist groups, Italian-American leftists, and the Communist-linked American League against Against War and Fascism, the event’s sponsor.

Often relegated to the margins of history, the Italo-Ethiopian War of October 1935 to May 1936 brought the world home for America’s Black and Italian communities. It strengthened sentiments of belonging that transcended national boundaries, and sensitized many throughout the Black diaspora to the stakes of anti-racist and anti-Fascist struggle. New York City, with its large African-American and Italian-American populations, became a hub of activities. Photographs tell the story of how a conflict with global consequences unfolded at the local level.

Ethiopia had a special significance for many in the Black diaspora. It was an ancient center of Christianity and a symbol of anti-imperial defiance. At Adwa, in 1896, Ethiopians forced Italian armed forces to retreat, putting an end to Italy’s first attempt to occupy the country. Ethiopia’s Emperor, Haile Selassie I, enjoyed global fame. He inspired Rastafari, a cultural and religious movement that considered him as a messianic figure. For millions, the invasion of Ethiopia imperiled Black freedom and dignity everywhere.

Black and White anti-racists and anti-Fascists came together to organize. Nurse Salaria Kea of Harlem Hospital collected funds for a 75-bed hospital and sent two tons of medical supplies to Ethiopia. Samuel Daniels, head of the Pan-African Reconstruction Association, toured New York and other major American cities to recruit volunteers. Soon the State Department reminded community leaders that it was illegal for American citizens to fight for a foreign power. Yet two Black pilots, Hubert Julian and John Robinson, found their way to Ethiopia to assist.

Civic education initiatives abounded. New York University, Columbia University, and Brooklyn College held rallies and debates. Many of these were organized by the Universal Ethiopian Students' Association, which took inspiration from Marcus Garvey's Universal Negro Improvement Association, then the largest movement in African-American history.

More than 10,000 attended a rally held at Madison Square Garden on September 26, less than a week before the invasion, to hear civil rights leader W.E.B. Du Bois and others denounce Fascist aggression. The rally was also a demonstration of racial unity. Whites, including many anti-Fascist Italian-Americans, made up three-quarters of the audience that cheered the destruction of a 20-foot Mussolini effigy. Ethiopia built bridges between some New Yorkers, and drove others apart.

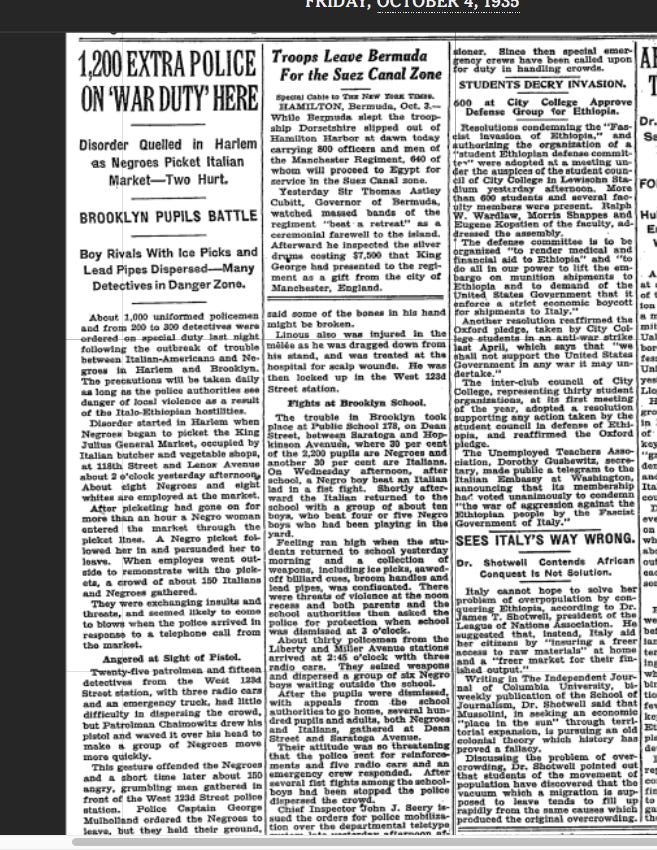

In fact, while some Italian-Americans in New York protested Mussolini, others embraced him. When the invasion of Ethiopia began on Oct. 3, Italian-American and Black students brawled at Brooklyn’s P.S. 178, and a Black protest of Italian vendors at the King Julius General Market on Lenox and 118th Street turned into a riot. The New York City Police Department deployed 1,200 extra policemen on “war duty” to address the unrest.

Italian-American communities stepped up their own activism. They recruited combatants and raised funds, donating wedding rings that would be sent to Italy and melted down for armaments. At a December 1935 rally in Madison Square Garden attended by 20,000, Mayor Fiorello La Guardia presented the Italian Consul General with a $100,000 check, part of a total $700,000 raised during the conflict.

Admiration for Benito Mussolini fueled much of this support. A celebrity in the U.S.,Mussolini had had a monthly column in Hearst newspapers since the late 1920s. A month into the war, as airplanes unleashed tons of poison gas, killing thousands of Ethiopians, a Time magazine cover depicted Il Duce with his sons, ever the family man. When Italy declared victory in May 1936, Italian-Americans celebrated in Little Italy.

African-Americans and White anti-imperialists responded to the announcement by marching again down Lenox Avenue. In Midtown, the American League Against War and Fascism picketed the Italian Consulate.

When exiled Emperor Haile Selassie spoke to the League of Nations in June 1936, he denounced “the deadly rain” of chemical weapons that killed his people. But the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, and Adolf Hitler’s expansion within Europe, made Ethiopia’s plight of marginal concern. Many in the African diaspora knew better: Ethiopia, not Munich, was the first example of Western appeasement of Fascist aggression. An estimated 250,000 Ethiopians were killed before the Allies drove the Italians out of the country in 1941.

The Italo-Ethiopian War may remain an obscure event to many Americans. Yet it propelled Black and White activists to take to the streets of New York and other cities across the world. It merits our attention as we navigate our own fateful time of mass protest against institutionalized racism and authoritarian aggression.

Another amazing, inspiring story that I am so grateful to hear about. I am continually amazed to see photos of people from almost 100 years ago that look and sound like truth tellers in our present day who are vilified as radical anarchists, as surely these folks were back then. I appreciate your showcasing the story, Ruth, and hope it moves the needle toward recognition of the threat of fascism in the minds of present day citizens. More, more, more!

Thanks Ruth. I like your statement that the first example of Western appeasement of fascist aggression was not Munich but Ethiopia. Also obscure and probably not that well known to many Americans was a Nazi rally held in Madison Square gardens in 1939 and attended by 20,000 people. It seems some element of fascism and authoritarianism is always present in societies. These elements used to be kept below the surface and out of the main stream. But since 2015 we're seeing it rise all over in America.