Visualizing Fascism; Bringing Fascist History to the Screen

Welcome back to Lucid, and hello to all new subscribers.

As some of you know, I am a historical consultant for film and television. I was the sole consultant on Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio (2022), which was set in Fascist Italy and won an Academy Award. I’ve been waiting to tell you about my latest project: “Hitler and the Nazis: Evil on Trial,” a docuseries directed by Joe Berlinguer. It premieres on Netflix on June 5.

Here is a Variety article about it, with comments by Berlinguer, and here is the trailer. I was supposed to be on camera as an expert as well, but I was ill on the day slotted for my filming, so my presence registers in other ways. I will be happy to discuss my work on the series once it airs.

Here is a just-published profile in NYU’s Scope magazine of my work for film and television “to ensure that history doesn’t repeat itself offscreen.”

On this subject, here are some thoughts adapted from an essay I published in the book Visualizing Fascism. It asks us to think critically about the images of past dictatorships that we see. What from those regimes is hidden from our view, even today?

_______

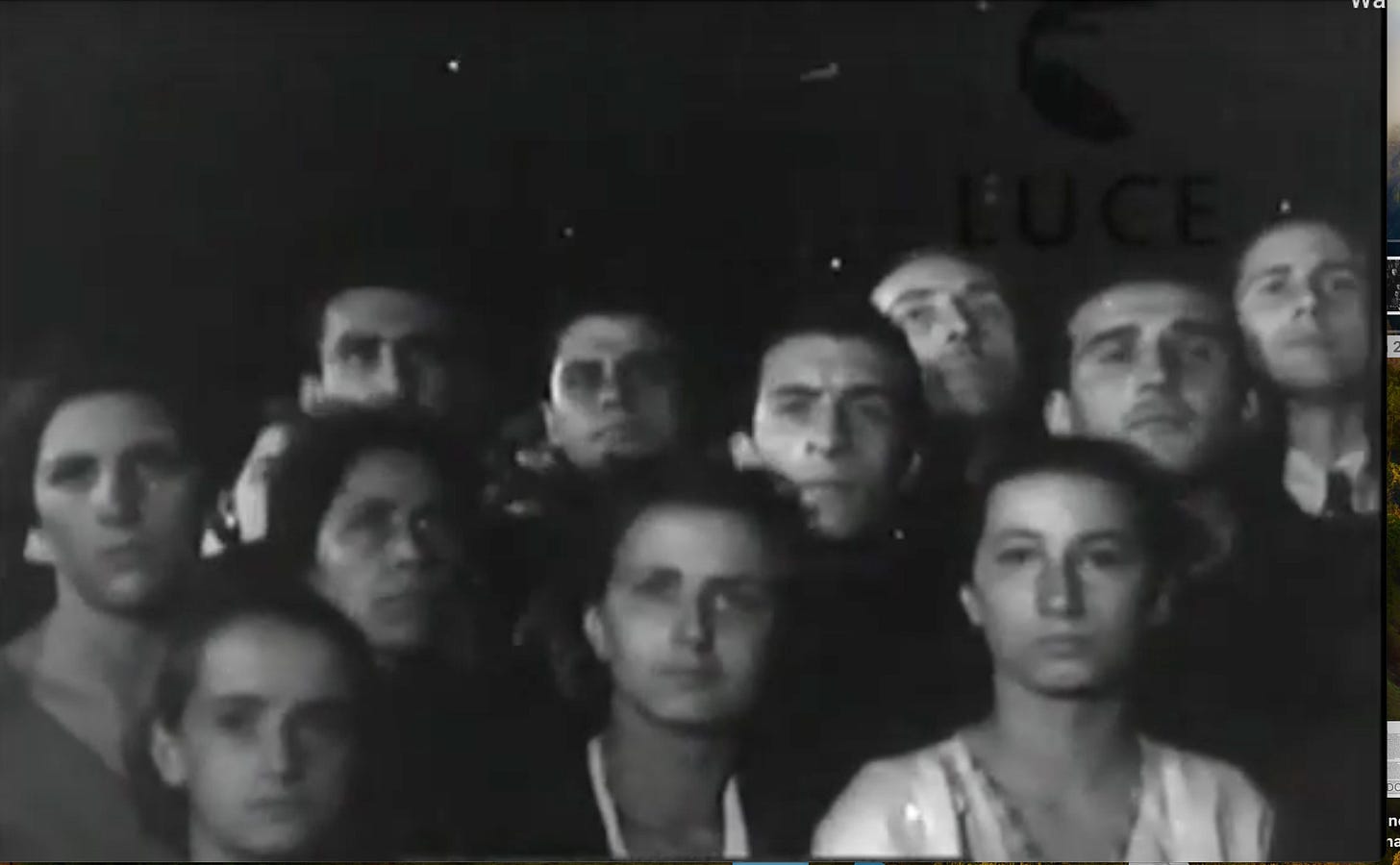

Most of us can easily conjure pictures of the regimes of the interwar and World War Two years. Uniformed men on the march, children performing in sports arenas, and the dictator in his uniform likely figure in this repertoire. Yet there are other ways of visualizing fascism, such as focusing in on the anonymous “faces in the crowd” that populate so many fascist photographs and moving images.

While we cannot know what ordinary people were thinking, these faces deserve our attention. They can remind us of what these regimes most feared and what the Leader could never fully control: the humanity and agency of the individual.

The historical profession still displays a certain reluctance to use images as anything more than supplements to written documents. This means we miss chances to learn what only images can tell us.

The visual communicates in ways written documents cannot, and images have their own ways of narrating the past. Images convey facts, but also moments of perception and emotion that can be hard to put into words. The stories they narrate don’t always map onto what’s deemed appropriate or worthy of narration by the historical establishment.

So let’s take a Fascist newsreel of a state rally and see what happens when we go into the crowd. This was one of the most important rallies of the Fascist era: the crowd was assembled in Piazza Venezia in October 1935 to hear Mussolini’s announcement of the invasion of Ethiopia. Italian troops were already ready to strike at the Ethiopian border, so the rally was largely performative in nature. The regime wished to show the world that the invasion had a popular mandate.

The presence at the rally of cameras of the Istituto Luce, the state film and photographic agency, underscored that the audience was part of the spectacle, no less than Mussolini. In the spirit of the Nazis’ 1934 Nuremberg rally, people assembled during the day, giving the press ample time to track their activities. For dramatic effect, Mussolini delayed his appearance until nightfall.

As always at mass rallies, only a tiny fraction of those present actually saw Il Duce. Most people looked in the direction of his voice, which was transmitted by loudspeakers, as below.

The second image is a frame enlargement from a pan of the crowd. While the newsreel released to the public had a cheering soundtrack, the closed mouths and expressions of these members of the crowd suggest silence, at least while the regime’s cameras were filming them.

Their faces are sober and alert: after all, impending war meant the probable drafting of husbands, fathers, and boyfriends. Or maybe they have merely arranged their faces into the neutral expressions that one adopts when living in a police state, especially when you are being filmed.

Yet the directness of their gazes communicates a calm dignity. In the midst of a Fascist spectacle announcing that Italians will be sent off to Ethiopia like cattle, they are choosing not to smile or cheer. And with over a million men mobilized over the course of the next nine months, it’s not impossible to imagine that some of these men would be injured, or even killed, one year later.

With the soundtrack silenced, and our attention on the faces of the crowd rather than the leader, we can start to have a sense of how people managed in a police state that infused everyday life with anxiety and dread —states of mind that today’s admirers of Il Duce would like us to forget.

I’ve been thinking about how the average Italian or German citizen felt while watching Hitler and Mussolini ascend to power. Did they have the same sense of dread I have now worrying about the country my grand children will inherit?

Your words with the pictures certainly made me feel what they must have gone through. I would imagine that a numbness sets in so you don’t cry or panic. There’s also a look that looks like them holding their breath waiting for the other shoe to drop. Thank you. I really an looking forward to the new film. I’ve been going through old films and documentaries that are streaming on about the startup to the end of the War Ii. I’ve been assuming that some are weak on the facts.

I know I cannot prepare myself or my family for the worst possibilities snd perhaps it might be too overwhelming.