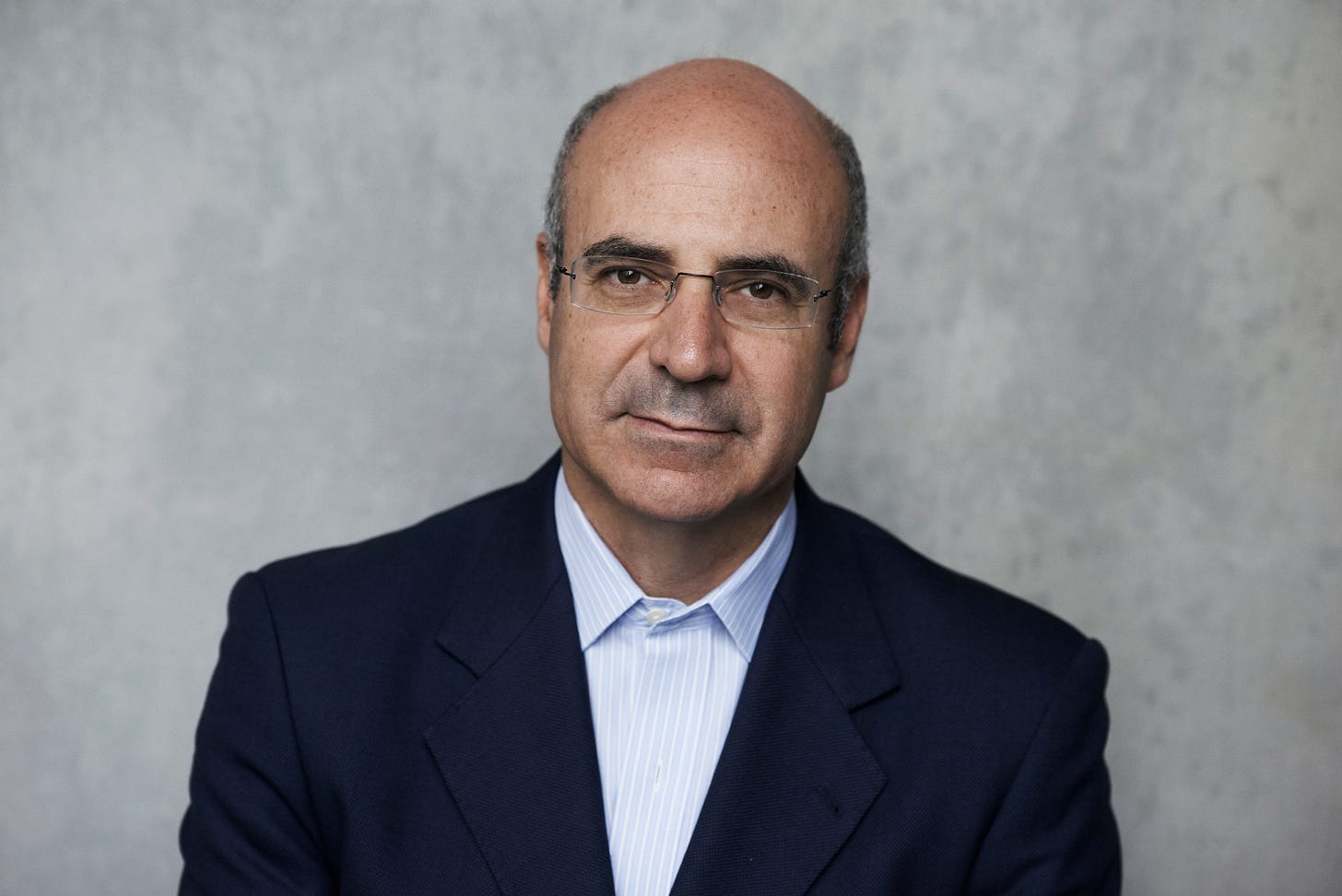

Lucid Interview: William Browder & Live Chat Info

Fighting Corruption, Protecting Human Rights

I'm very pleased to present my interview with William Browder, founder and CEO of Hermitage Capital Management. This interview, from March 1, 2021, was edited for clarity and flow.

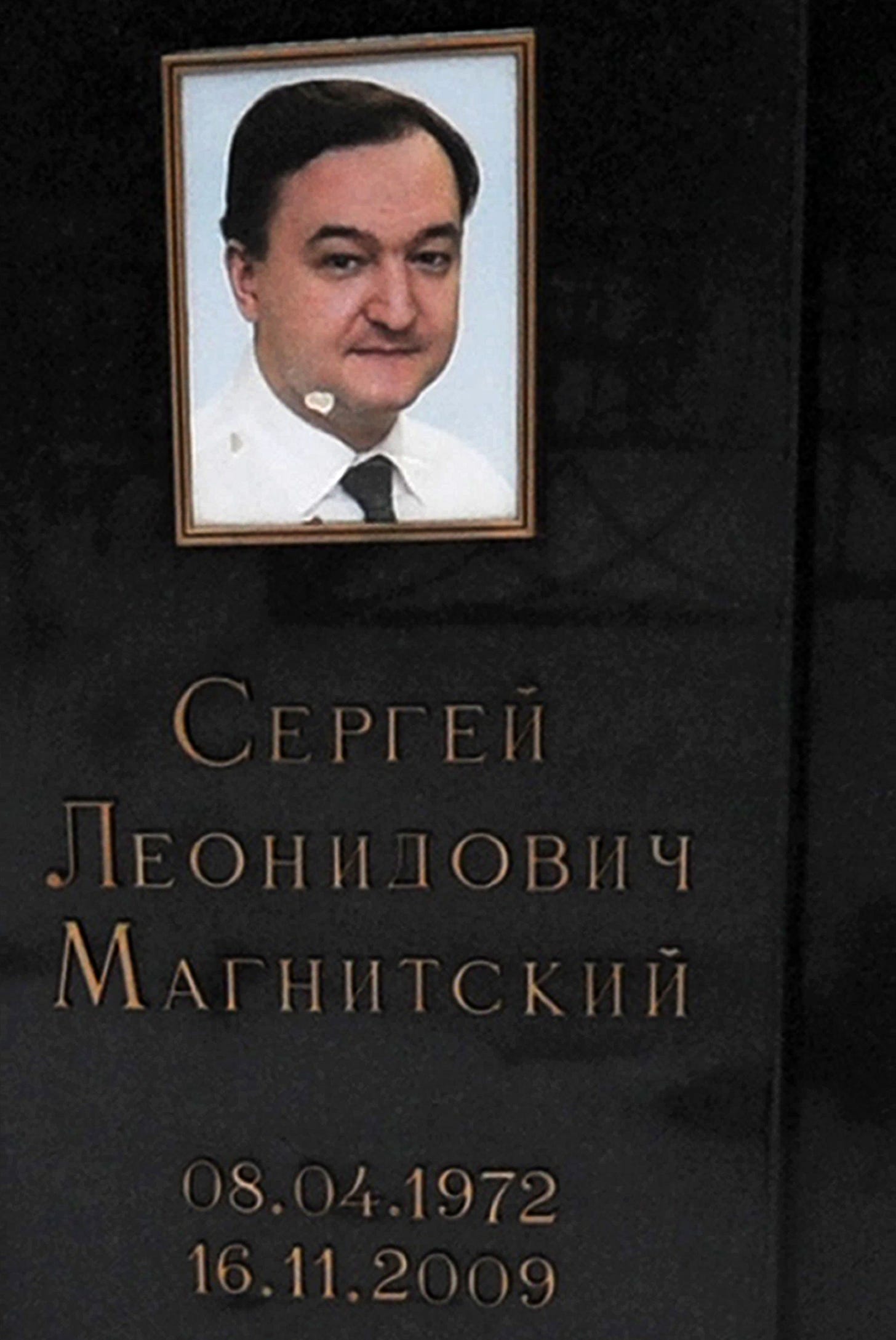

Browder was the largest foreign investor in Russia until 2005, when Vladimir Putin's government denied him entry to the country after he and his Russian lawyer, Sergei Magnitsky, exposed a government fraud scheme. Magnitsky was arrested and his beatings and lack of medical care led to his death in a Moscow prison in 2009. The Kremlin claims he died of a heart attack.

Browder was instrumental in the passage of the 2012 Magnitsky Act in the United States, which sanctions human rights abusers. Magnitsky legislation has now been passed in at least nine countries and in the European Union. Browder's 2015 New York Times bestseller, Red Notice, recounts his experiences and his ongoing fight for justice for Magnitsky. Browder faces death threats for his activism, and his name is on Putin's latest enemies list, released in late March 2021.

RBG: You said in a December 2020 interview that "human rights abuse and kleptocracy go hand in hand," referring to the limitations of the EU Magnitsky Act, which does not cover corruption. Can you talk about why the struggle for human rights and against kleptocracy must be entwined?

WB: My own experience created the realization that they were entwined. I was being targeted by a corruption scheme by a bunch of government officials. My lawyer, Sergei Magnitsky, figured out how Russian officials stole $230 million of taxes that we paid to the Russian government. He testified against the officials, who then arrested him and put him in pretrial detention. They tortured him for 358 days until he was killed. So this story encapsulates the interaction between corruption and human rights abuse: Magnitsky uncovered the corruption, he exposed it, and then in retaliation he was abused, tortured, and killed.

WB: What I've seen is that this is not unique, this is more or less standard operating procedure in dictatorships. I think it's almost unheard of to have someone who is ready to kill who doesn't also feel entitled to steal. And so you end up in a situation where sometimes the best way of targeting people is going after their corruption rather than their human rights abuse because the corruption is easier to prove than actually getting a picture of them pulling the trigger or ordering the torture or whatever.

RBG: That's so true. Dictatorships like Augusto Pinochet's Chile also became more expert over time at adopting torture techniques that didn't leave lasting marks on victims - less evidence for human rights investigators. But it was harder to refute corruption charges, like Pinochet using public funds to build a country home in El Melocotón.

WB: The thing is that corruption generally means sending money somewhere, and it leaves an indelible trail, and it leaves that trail in a [foreign] jurisdiction that they don't have control over, because they are trying to get their money out of the country.

RBG: Exposing corruption is key to busting some cherished authoritarian myths, like the idea that autocracy is "good for business," or that Putin defends Russia against Western immorality. So I wanted to talk about Putin's predation of Russian businesses, which you have personal experience with. The scope of the persecution and seizures is staggering. Between 2002 and 2012 over 70,000 business owners were jailed or faced criminal proceedings on technicalities or fabricated charges of tax evasion or other crimes. These practices continue today.

WB: In fact, there is no business in Russia that is not targeted. The most popular higher education tracks among Russians involve either going to FSB [Federal Security Service] academy or the Interior Ministry academy. This is because if you get a job in FSB or Interior you have the power to arrest people and those powers are then used to generate huge economic gains. As a result, there's a very unsteady equilibrium in a place like Russia: if you have money, it's very likely someone is going to try and take it away from you. Almost universally, the oligarchs of Russia become delegates and business partners of Putin or those close to him.

RBG: Why don't we hear more about these predatory activities?

WB: A main reason is that when they decide to go after someone, they don't just take their business away, they take their liberty away, and oftentimes they kill those people. And so if you have a person who was once wealthy and then has their property taken away and is in jail they can't speak about it. Add while they are in jail their reputations are fully tarnished and so even if they did speak about it no one would believe them. The general approach is not just to appropriate their property but to destroy them and everyone close to them. So you don't have that many people with the ability to tell the story. Most of them are either taken out of public circulation or are dead.

RBG: Well that's a perfect repressive system.

WB: I have enough contact with those who are victims of this to see it play out over and over again. Right now I am advocating for a Russian family that fled to Guatemala. They owned a pulp and paper business in Russia, and after it was expropriated they thought they could hide from their persecutors in Guatemala, which does not have an extradition treaty with Russia. But the Russians eventually tracked them down there and have corrupted the Guatemalan authorities, who sentenced the father to nineteen years in prison and the daughter and the wife each to fourteen years.

I was recently asked by US State Department personnel - people familiar with Guatemala but not Russia - why the Russians would go to all this trouble. I told them that the Russians can't just take the property away, they have to fully and totally destroy the family. First, so that no one will speak about what they do, and second, to make an example of them, so that when someone else is approached for their property they will just willingly hand it over out of fear.

RBG: Let's talk about the Magnitsky legislation that came into being as a result of your efforts to create a mechanism that would use economic pressure from abroad to curb criminal behavior. In fact the role of foreign enablers in authoritarian corruption - the banks, law firms, and PR firms these states use - is not highlighted nearly enough. And this allows the hypocrisy of "anti-globalists" like Putin, who depend on global offshore finance networks to hide their money, to continue. And of course, here in the States, there is no bigger globalist than Donald Trump [Browder laughs], whose business model is all about licensing his name abroad. Trump was acquiring Chinese trademarks well into his presidency.

How does Magnitsky legislation work to make collaborating with autocrats less acceptable or desirable?

WB: The Magnitsky Act has been a watershed moment for a lot of these enablers, particularly the banks. Here is a real-life scenario. A Russian who was sanctioned using the Magnitsky Act had a lot of American dollars in a Swiss bank. When he was sanctioned he wanted to move those dollars to a Russian bank, and he thought he'd be okay because the money was in Switzerland, which does not impose the Magnitsky Act. But the Swiss bank was subject to US law when it came to violating US sanctions because they have operations in the US. So if the Swiss moved any of the dollars to Russia they would be subject to US Treasury fines to the tune of three times the amount of dollars they wanted to transfer. So the bank would pay a heavy fine for moving this Russian's money.

So the CEO of the Swiss bank told his account officers to fire all Russian oligarch and potential human rights abusers among their clients so the bank would never face this situation again. So instead of wining and dining Russian oligarchs, the Swiss bank refused to even do business with them to protect its own economic interests.

RBG: While Trump was in office there was far less political will to hold Putin accountable, even though the US Magnitsky Act remained in force. Do you see the Joe Biden administration as an opportunity for change?

WB: we have to distinguish between Trump and his government. Trump was a complete monster about Russia. He validated Putin and he did Putin a number of favors that Putin could not have dreamed of, like raising the idea of the US leaving NATO, withdrawing the US military from northern Syria, and many other things, not least refusing to condemn the poisoning of Alexei Navalny. So Trump's actions were abhorrent when it came to Russia.

The people who worked for Trump deserve some credit, though. In 2018 the US government sanctioned seven of the biggest Russian oligarchs for their closeness to Putin and their roles in US election interference. That action was just monumental, and it caused extreme damage to Putin and to Russia. During the Trump years the government also rolled out the Global Magnitsky Act and sanctioned over 200 entities and individuals - the Treasury and State departments should be given for that. I braced myself every time Trump opened his mouth about Russia, but I was pretty satisfied with the actions of the government. We'll have to see what happens with Biden. It's not a sort of binary thing in which one guy is all good and one guy all bad. Biden has not sanctioned MBS [Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman] for having the journalist Jamal Kashoggi killed, and he should take the hit for that. Nor did Trump sanction MBS. So they both took the same action.

RB: With Trump out of office, America has a window to address issues of government ethics and corruption, including failure to report foreign financial and other interests. What are the consequences of not standing up for accountability right now?

WB: Former French president Nicolas Sarkozy was recently sentenced to prison for corruption, and France does not practice the mass incarceration of the US, which has the highest per capita rate of prisoners [655 per 100,000 inhabitants] in the industrialized world. So the US can certainly enforce the law rigorously and to its fullest extent for illegal actions committed during the Trump era. If it doesn't, it destroys any concept of the rule of law.

RBG: Should the Trump experience lead America to require more vetting of presidential candidates, for example requiring them to show their tax returns and reveal their indebtedness to foreign parties?

WB: The system worked very well in the States until someone like Trump came along. It was sort of an honor system, and he decided just to throw all that out. And so Trump proved there are weaknesses in the previous system that must be addressed and codified. Before running for office, individuals should be required by law to show their tax returns. And violators of the Foreign Agents Registration Act should be given prison sentences.

RBG: As someone who lives under conditions of duress, with recurring death threats, how do you keep your serenity? It would be hard to engage in the kind of work you do without a sense of balance and resolve.

WB: I have actually found that fighting for justice is infinitely more satisfying than fighting for money. Even though what drove me to this fight for justice was a terrible tragedy, in which a young 37 year-old lawyer was tortured to death, it has given my life a mission and a meaning that gets me out of bed with full vigor and enthusiasm every day to try and further my goals, including trying to make life worse for the bad guys. And that's a life worth living.

Looking forward to it!

Great interview! Browder is coherent and articulate.

He makes good points that sanctions work, and how. Putin particularly hates them (and consequently, Browder) because sanctions target his ability to protect the graft he allows and channels in order to maintain loyalty, and consequently, his power.