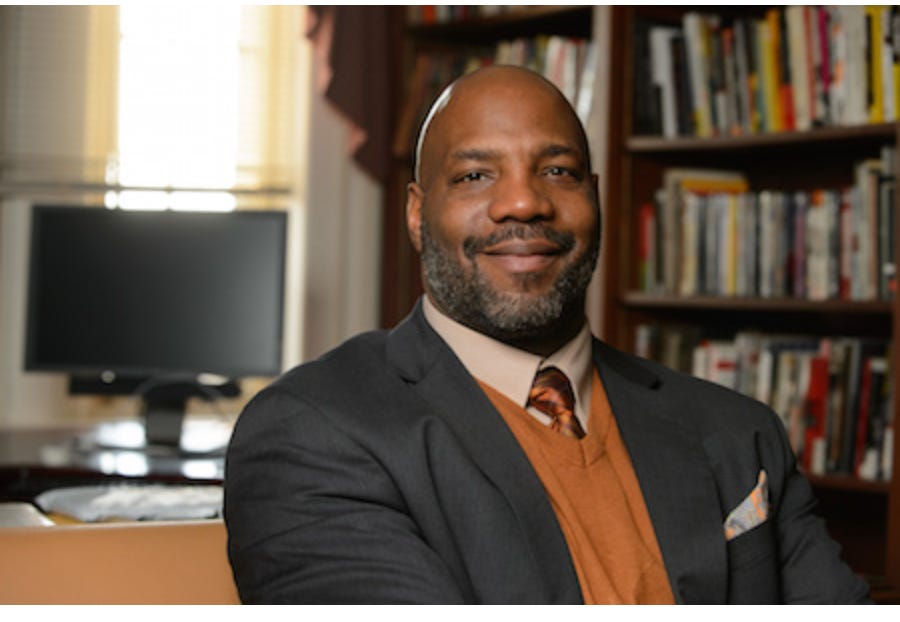

I'm pleased to bring you this interview with Jelani Cobb, who is the Ira A. Lipman Professor of Journalism at the Columbia School of Journalism and a staff writer at The New Yorker. He is the author of several books, including The Substance of Hope: Barack Obama and the Paradox of Progress, and the editor, with David Remnick, of The Matter of Black Lives, which brings together writing on race and racism from The New Yorker. He won the 2015 Sidney Hillman Prize for Opinion and Analysis Journalism and was a Finalist for the 2018 Pulitzer Prize in Commentary. Our conversation took place on Dec. 21, 2021, and has been edited for clarity and flow.

Ruth Ben-Ghiat (RBG): Some of the essays in The Matter of Black Lives discuss how we talk about and define race and racism. I was interested in your essay about how former President Barack Obama used the term "mixed race" to speak about his heritage, and this made him more acceptable to White people, even as Blacks considered him to be African American.

Discussions about race often leave aside mixed race people, although people of "Two or More Races" are projected to be the fastest growing category of Americans, according to the latest census. Fear of such "mixings" is everywhere in the history of global racism, and it has often fueled political reactions like the one we're living through now.

Jelani Cobb (JC): The status of mixed race people is complicated, as is even the existence of the category of mixed race. Barack Obama had a Black parent and a White parent, and he visually looks like an African American or person of African descent. But in some ways, politically, his White ancestry and White parentage made him palatable in a way that he might not have been if he had been an African American with two visibly Black parents.

It's not gone unnoticed that the highest and second highest occupants of political office who are people of color have been Barack Obama and Kamala Harris, both people of African percent, but both people who have a non-Black parent.

The reason why I say that's a complicated categorization and some African Americans kind of resist the distinct category of mixed race is the fact that the Black population of the United States overwhelmingly has White ancestry. Most of that ancestry entered our lineage during the course of slavery, when rape and other coercive practices were commonplace. And it really becomes a luck of the draw about how much of this White ancestry is visible. In my own family, I know about my White ancestors, and so I would technically be considered mixed race. Yet no one would ever think of me like that, because I have two Black parents.

RBG: You wrote about Rev. Dr. William J. Barber II in your edited book. I follow his inspiring work closely, because I've always felt that faith has to be part of any successful pro-democracy movement in America. I also find the election of Reverend Raphael Warnock to the Senate (D-GA) very interesting. He is one of only two clergy in Congress, the other being James Lankford (R-OK). Revs. Barber and Warnock represent two very different paths to influence and mobilization by people of faith.

JC: Even going back to the civil rights era, the success and visibility of Martin Luther King Jr. was by and large driven by the fact that he was a member of the clergy. There's a very long tradition of people who have specifically argued on behalf of a more egalitarian society through the lens of faith, and made theological arguments that were as much social as they were theological, pointing to the idea of segregation and racism and discrimination as sins.

This language allowed people to understand those problems in a way that they had not before. I think that that's very valuable and very useful, and the work that that Reverend Barber has done with the Poor People's Campaign is a direct extension of that.

I've been very impressed with the way that he has used a theology of democracy, seeing equality and the need to protect the most vulnerable as a direct product of Christian ethics, kind of the way that Jesus lived and approached the world.

Now of course it's complicated by the fact that the most reactionary elements in American society have also anchored themselves in a particular theology and have weaponized faith in some ways that continue to be dangerous. This is not entirely surprising, given that people also used to argue that segregation was a biblical mandate, or that slavery was consistent with Christian ethics. What we're looking at now is essentially a theological debate between progressives and reactionaries.

RBG: Only some faith traditions are suitable for use by authoritarians. Once illiberals get power, they often marginalize faith traditions based on social justice and progressive values.

JC: It's been fascinating to see the astounding contortions that conservative Christians tied themselves into to justify Trump, a person that reflected not a single one of the ethics that they professed were central to their cause. It's really a theology of power. And he was a mechanism by which they could gain power.

RBG: Will we see another round of mass nonviolent protest in 2022? A tragic and traumatic event, the killing of George Floyd, sparked the Black Lives Matter mobilizations in 2020. If you look at the history of resistance, there is often a specific event as serves as a trigger.

JC: It's hard to predict because you don't know which spark is going to light the kindling. What I think is almost certain is that the mechanisms being put in place in Republican-controlled legislatures to deny people democracy will generate large scale social unrest. It's almost like the theatrical principle of Chekhov: If you introduce a gun in the first act, you have to fire it by the third act. Something has to happen. Republicans have built this machinery to steal elections. They're going to use it, they're not just going to let it sit there, and there will be a reaction.

RBG: What's your take on Jan. 6th and what it means for Trump's extremist followers? My work on fascism leads me to see it as the foundational event of a new sacred community, with martyrs like Ashli Babbitt. I'm curious how you see it as an American historian.

JC: I see it in the same sense, and going back further, one of the things that alarmed me about Charlottesville [the 2017 Unite the Right rally] was that these people had found each other. I said at the time that irrespective of whatever happened, they now have a new esprit de corps, they feel like they are part of a group and they are molding an identity around that group. January 6th furthered that. People came together in a militant and violent fashion and they were able to invade the Capitol.

You had the Nazi sympathizers, the person with the Auschwitz shirt; you had Confederate sympathizers; Oath Keepers and Proud Boys; and hardcore Trump constituents who might not fit neatly into any of those categories. It really was this kind of cross section of disgruntled reactionary figures who now have each other's cell phone numbers and email addresses and they have congealed into a movement. And that's something we're going to have to reckon with for the foreseeable future.

I'm angry and frustrated by the authoritarian predicament we're in as a country--on the edge of losing its democracy. There are a lot of reasons for it staring with with 40 years of neoliberlism started under Ronald Reagan. But what I am focusing most of my blame on these days are the inherit structural flaws of the constitutional framework set up by our founding fathers. Namely, they are things like the electoral college and the senate. Both are inherently anti democratic because they allow minorities to rule over majorities.

Democrats have won seven out of the last eight popular votes in national elections, the 50 Dems in the senate represent 40 million more people than the 50 Republicans in the senate etc. Dems keep winning majorities but barely have jack to show for it, look at the reactionary 6-3 conservative majority on the supreme court McConnell engineered. It is nowhere close to being in step with most Americans by a long shot. Just in the last 20 years two Republicans got elected President despite losing the popular vote.

Each time the minority Republicans got power from the antidemocratic electoral college or aggressively gerrymandered districts, they extended it to the Supreme court to make it partisan, and to pass voter suppression laws on the state level and to the elevation of state's rights over the federal government and juridical review.

We are where we are I would argue because of the systemic flaws of the constitution and its electoral college that allows minorities and candidates with the fewest votes to take power over majorities. It is repugnant to any notion of democracy. Yes there were some reforms and voting rights measures but they got reversed by conservative courts. It wasn't enough. Look where we are now. The seeds of the democratic experiment's own destruction were sown into it from the beginning by the founding fathers.

I'm a great admirer of Mr. Cobb's body of work, thank you for the interview. I hope that future historians, perhaps in democracies that remain post-2024, will find a way to explain the passivity of Democratic party leaders as this movement grew...in plain sight, for 5 years. FBI Director Wray decided that ignoring the terrifying reality was more politically expedient than facing the complex issues required to define domestic terrorism and prosecute domestic extremists. The GOP base is so blinded by their twisted form of 'political faith' that they're risking hospitalization and death for their cause, while Democratic leadership gives cover to our feckless FBI leadership by pretending that the stakes aren't as high as they are. I feel as though we're on the cusp of widespread vigilante assassinations and no one is taking a step to change the course. Perhaps I'm alone in what I see in the abyss...I hope so, but my deepest fears have manifested for 5 long years.