Welcome back to Lucid, and hello to all new subscribers. Today’s essay adapts the sections of Strongmen that relate how Adolf Hitler came to power. You might also be interested in the documentary series Hitler the Nazis: Evil on Trial, for which I served as a historical consultant. As many of you know, I work as a historical consultant for film and television.

_____________________

The Third Reich began the way it would end: in flames. The fiery landscapes of World War I forged many of the men who followed Adolf Hitler, torches in hand, as he promised them a new Germany. One fire, the Reichstag-gutting blaze of February 27, 1933, proved particularly fateful.

While there is no consensus among historians about the fire’s origins, when Dutch Communist Marinus van der Lubbe was found in the building that evening, Hitler had an excuse to proceed with mass arrests of leftists and strip all Germans of civil liberties. “You are now witnessing the beginning of a great new epoch in German history,” he told the British journalist Sefton Delmer that night as they watched the flames consume Parliament. “The fire is the beginning.”

Hitler had been in his early twenties when he made an important discovery. He felt most alive when losing himself in something he found sublime, like a Richard Wagner opera or the sound of his own voice. He had moved to Vienna from Linz after his mother’s death, and while his desired careers as a painter and architect went nowhere (he was rejected twice from the Academy of Fine Arts), he found he had a talent for captivating and cowing people with extended verbal tirades.

Hitler’s ambition led him to Germany, where he won two Iron Crosses for his service in World War I. The striking oratory that had helped him become the head of and the Nazi Party now attracted attention. From his Munich base, he harangued against Jews, the “black parasites of the nation” who might have to be placed in “concentration camps”; Marxists; war profiteers; and foreign powers, all of them out to rob Germany of its future.

Hitler’s vocal and emotional force brought to him collaborators like Joseph Goebbels, later his Minister of Propaganda. “What a voice. What gestures, what passion. My heart stands still…I am ready to sacrifice everything for this man,” Goebbels confided to his diary after hearing Hitler speak in 1925.

Convinced of his providential mission, Hitler took to holding multiple rallies in a single evening, usually arriving late and with an entourage, like the divo he was becoming. The SA (Storm Battalion), a paramilitary force co-founded by Ernest Röhm that drew its members from World War I elite shock troops, provided Hitler with protection at these rallies, and then grew to become the NSDAP’s own hit squad.

Runaway inflation and Germany’s default on reparations payments, which led the French and the Belgians to occupy the Ruhr area in 1923, increased the sense among some Germans that extraordinary action was needed to save the country. The Versailles Treaty, which blamed all of the conflict’s damages on Germany, fueled charges by Hitler and many others that foreign and domestic elites had “stabbed Germany in the back.”

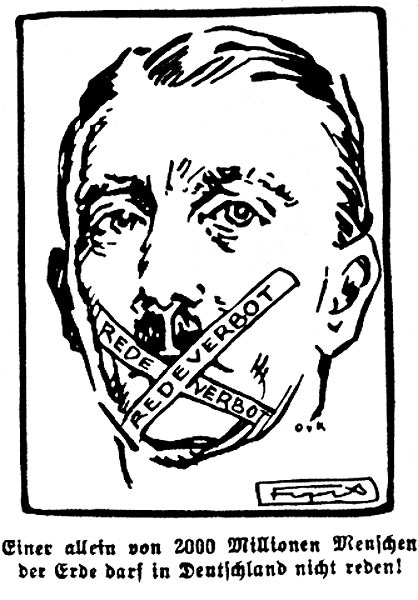

Yet Hitler had little traction beyond his small base of fanatic followers. His failed November 1923 Bavaria beer hall putsch had damaged his reputation and sparked a prohibition on the NSDAP holding office. No press but the NSDAP’s own would publish Hitler’s lengthy work Mein Kampf (My Struggle), which he wrote while in prison in 1924 for the putsch attempt.

Hitler also had no live audience, since his hate speech had gotten him banned from public speaking in almost all German states. A 1926 NSDAP poster calling for a protest against the ban depicted him as a populist truthteller muzzled by the “crooks and fat cats” who controlled Weimar democracy.

Hitler redoubled his efforts to obtain Benito Mussolini’s counsel on how to bring a fascist takeover to Germany. Il Duce ignored the Austrian’s requests for his photo, but Hitler was undeterred. He installed a bust of the Italian leader on his desk, dismissed remarks from NSDAP associates that he suffered from “Mussolini-intoxication,” and pestered Mussolini’s Berlin liaison, Army Major Giuseppe Renzetti, for a meeting.

Hitler had already learned from Mussolini the importance of making himself palatable to a larger public to gain entry into the political mainstream. In 1925 he promised to abide by the Weimar constitution to get the NSDAP ban lifted, and his speaking ban ended in 1927.

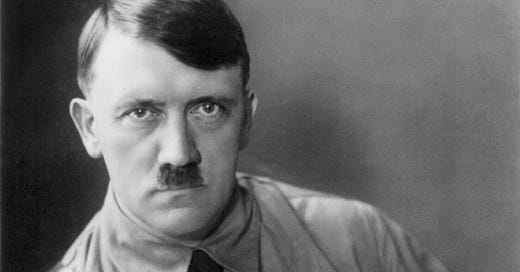

He also hired Heinrich Hoffmann, who later became his official photographer, to refine his image. A 1929 Hoffmann portrait highlighted his intensity and masculine capability. The businessman Ernst von Hanfstaengl introduced this cleaned-up Hitler to the moneyed social circles that mattered.

Hitler was ready when the economic crisis hit Germany and the NSDAP became the second largest party in the 1932 elections, sandwiched between the Social Democrats and the Communists. At last Mussolini sent him an autographed picture, and the NSDAP sold 287,000 copies of a slimmer edition of Mein Kampf between 1930-1933.

Hitler’s audiences multiplied as he exerted what observers saw as “an almost mystical power of attraction” at rallies, unleashing frenzies of raw emotion that expressed Germany’s pain and anxiety. “We don’t want to hear anything more about the government, we want only ADOLF HITLER as our leader, as the sole strong hand, as dictator,” wrote the Silesian official P.F. Beck to Hitler in 1932.

As in Italy, the action of a few conservative elites, rather than popular acclaim, got the strongman into power. Around 1930, the media magnate and German National People’s Party head Alfred Hugenberg and the German President Paul von Hindenburg had begun to court Hitler, thinking he would support rearmament and help them subvert the left’s growing electoral strength.

In January 1933, on the strength of the NSDAP’s electoral showing, Hindenburg made Hitler Chancellor, allowing him to rule by decree, as had his immediate predecessors, rather than by parliamentary majority. German conservatives thought Hitler would be their tool. The industrialist and NSDAP funder Fritz Thyssen saw Hitler’s rule as a transition to restoring the German monarchy. “I, too, misjudged the political situation at that time,” Thyssen would write after fleeing Germany in 1939.

Having waited a decade to get into office, Hitler had no interest in following Renzetti’s advice to “make your moves carefully, and don’t rush.” The February Reichstag fire ensured that he didn’t have to. The building still smoked when Hindenburg issued an emergency decree ending freedoms of press, assembly, and more. Thousands of leftists were detained in prisons and warehouses while Dachau, the Reich’s first concentration camp, was being converted from an arms factory.

In March came the Enabling Act, which allowed Hitler to rule without consulting the Reichstag or the President. In less than two months, he had secured the ability to govern without any checks on the exercise of his authority.

This was likely no surprise to the Italian-Austrian journalist and writer Curzio Malaparte, whose 1931 book The Technique of the Coup d’Etat had predicted that Hitler would “corrupt, humble, and enslave the German people, in the name of German liberty, glory, and power” if he got into office.

Curzio Malaparte’s comment about Hitler’s relationship with his most faithful collaborators proved prescient and is a lesson for us today.

“He channels his brutality into humbling their pride, crushing their freedom of conscience, diminishing their individual merits and transforming his supporters into flunkeys stripped of all dignity. Like all dictators, Hitler loves only those whom he can despise.”

Additional References:

Hitler, Mein Kampf, trans. Ralph Manheim (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1999), 562.

It's the same playbook. Oligarchs grease the wheels for Trump like they did for Hitler. It's about chaos and in chaos you can steal, both money and power.

Horrifyingly prescient of today’s fascist movement.