"Divided. Dismal. Disappointment. Lost." American independent voters used these and other negative terms to describe the state of the country in a discussion the New York Times organized this past January. "Downhill, divided, doubting democracy, falling behind, and tuning out" was Democratic pollster Jeff Horwitt's summary of responses to a survey he and Republican pollster Bill McInturnff conducted that same month.

It's no secret that Americans feel pessimistic about the future. Profound exhaustion and grief due to the pandemic, worries about inflation and consumer shortages, and social interactions marked by turmoil and hostility have soured the national mood. A CNN poll of 1000 adults last week showed that only 10% of Americans feel "optimistic" about the way things are going in America, while 65% are concerned, and 21% are downright scared.

Pessimism, like optimism, can be contagious. To rebound from tragedy and respond effectively to threats against our freedoms, it's more important than ever to adopt the secret weapon of democracy protection: hope.

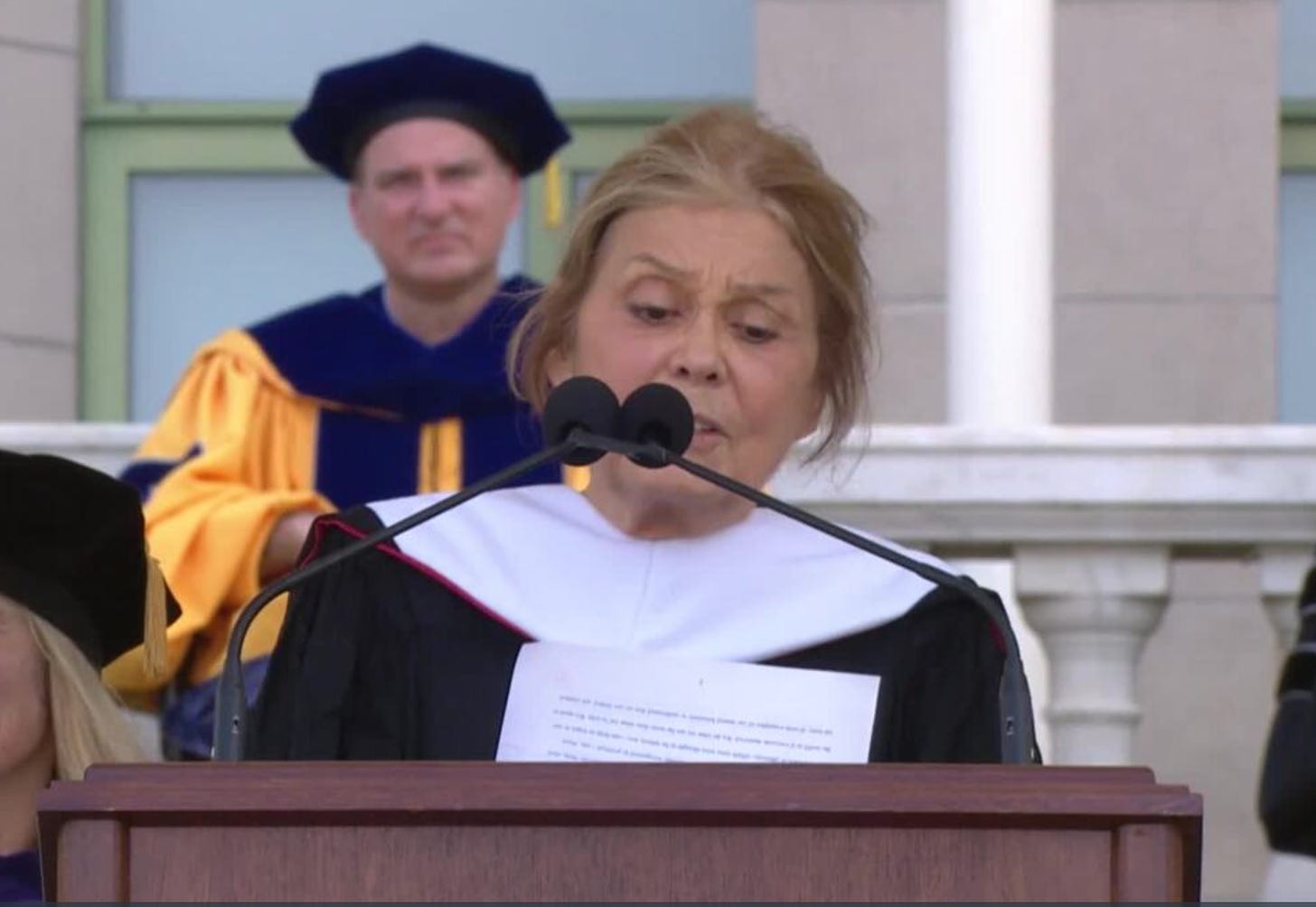

I was pleased to hear Gloria Steinem, speaking at Wesleyan University's 2022 commencement, place hope at the center of her remarks. Steinem, who has fought for women's rights for decades, might have had cause to feel depressed, given the recent Supreme Court opinion in favor of overruling Roe vs. Wade.

Yet Steinem declared herself a "hope-a-holic," and reminded her audience that hope is a practice as well as a faith: "a form of planning," in her words.

I was attending the commencement as a parent, but Steinem's speech also hit home for me as a scholar, since authoritarianism is a system of governance that revolves around defeating hope.

Authoritarianism breeds fear, through the use of state repression, but also cynicism that can shade into nihilism. If nothing matters, and nothing will ever change, then far fewer people will be willing to risk everything to fight for a more just society. It is easier to submit, whether that means staying silent about the persecution of your compatriots or about negligent state policies that result in mass death.

We are still reeling from the effects of four years of that negligence and callousness in America. “It is what it is," former President Donald Trump said on camera in September 2020 when Axios' Jonathan Swan told him of the pandemic's spiraling mortality rate. The emotional flatness Trump modeled was intentional, part of his re-education of Americans to put aside hope and accept the status quo.

Holding onto hope may seem quixotic or unrealistic to some in America today, given the mounting calls to violence, the radicalization of the GOP, the ascent of more election deniers to high office, and more. Why even vote, if the results will be refused or overturned?

Yet hope is an essential part of anti-authoritarian strategy. It is the antidote to a deadly fatalism, to what Eric K. Ward calls the Other Big Lie: "The idea that we have already lost. That the next civil war is inevitable. That we are helpless and hopeless in the face of all the bad news."

Having hope, Rebecca Solnit argues, does not mean embracing the idea "that everything was, or will be fine." Hope's power lies in its embrace of openness and possibility. "Hope locates itself in the premise that we don't know what will happen and that in the spaciousness of uncertainty is room to act. When you recognize uncertainty, you recognize that you may be able to influence the outcomes...It's the belief that what we do matters even though how and when it may matter, who and what it may impact, are not things we can know beforehand."

It can be difficult and discouraging to show up day after day to protest, or doggedly work on lawsuits, legislation, voter registration, opinion pieces, and myriad other things meant to save our democracy, without knowing if they any of them will have an effect. The American civil rights movement had an answer to this uncertainty--show up, and then show up again, and again, until the wrongs have been righted.

Acting without knowing if your efforts will yield results is a condition well known to democracy advocates living under authoritarian leaders abroad, where even small gains can be extremely hard-won. The Russian activist Boris Kagarlitsky reflects this tough history when he says, “Struggle does not always lead to victory, but without struggle not only can there be no victory, but there cannot even be elementary self-respect.”

I can't help but compare the mentality of the "resigned rejectors," as strategist Frank Luntz called the independent voters he spoke with for the New York Times, with the pragmatic and process-oriented advice of Steinem to a new generation of college graduates. "Just remember that what you do every day matters. What you say, what you encourage, what you oppose, what you imagine."

Political progress comes not just from grand legislative packages, but also from the daily actions that each one of us takes in the belief and hope that they will make a difference. That philosophy has contributed to the end of dictatorships abroad, as in Chile and Eastern Europe, and it can help us to resist threats to our democracy here.

Reference: Boris Kagarlitsky in Mischa Gabowitsch, Protest in Putin's Russia (Cambridge, 2013), 73.

Thought you might be interested in this short commencement speech on hope I gave in 2017 at the University of West Scotland. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8eFTbsbYlEA. There is no viable politics without hope.

Thank you Ruth. We have to believe that we have the wind beneath our wings. We have to believe that we are the team that is about to break thru and win. Everyone wants associate with the winning team. That is the cloth we must don every day. That is the movement and energy we have to cultivate. We are in the home-stretch until November and we have outreach and talk everyday.

"Do we stay within the comfort zone that we've grown-up in, --- or --- do we venture out and make new friendships and build new links with people who come from different communities?"

(not my quote, and forgive me I cannot find the source-info). This may be Emboo Patel, Interfaith America.